Florida rooftop solar change seems likely to pass, over pushback from solar industry

Jacksonville Today

By Brendan Rivers

This article originally appeared on Jacksonville Today.

On Feb. 8, Raina Greenfest jumped on a bus from Palm Beach to Tallahassee to try to convince lawmakers to vote no. She wasn’t heading to Florida’s Capitol to rally against one of the controversial bills dominating national headlines this legislative session, like restrictions on abortion or race-based education. Rather, she was joining others from across the state who were organizing against a bill by Fleming Island Republican Sen. Jennifer Bradley — a bill drafted by utility giant FPL — that would significantly reduce the economic benefit of installing solar panels on our roofs.

For Greenfest, dubbed “Solar Mom” by her peers, opposition is personal. Her livelihood depends on solar installation. “I’ve been in the industry for 12 years. I can just say, from my bird’s-eye view, that we made history,” said Greenfest after the day in Tallahassee. “I’m pretty confident it was the largest gathering of solar workers in one place in Florida.”

Their voices weren’t persuasive in the Legislature. The measure passed the full House on Wednesday and is headed toward a vote in the full Senate.

Sen. Bradley — whose political action committee Women Building the Future received tens of thousands of dollars from Florida utilities this election cycle, including $22,500 from FPL’s parent company NextEra Energy — and others who support her bill say it would save all power customers money. Opponents say the hit to Florida’s fledgling rooftop solar industry further hinders the Sunshine State’s already slow transition to clean, renewable energy — what climate scientists say is urgently necessary if humans are to avoid the worst impacts of a warming world.

Florida Sen. Jennifer Bradley in legislative session on Jan. 12, 2022, in Tallahassee | Phelan M. Ebenhack, AP Photo

Net metering

Bradley’s bill would change the policy called “net metering,” which the Florida Legislature unanimously enacted in 2008. Net metering requires utility companies to reimburse rooftop solar customers for the extra energy they generate for the utility in the form of a credit on their power bill. Under current rules, the state’s investor-owned utilities are required to offer a one-for-one reimbursement rate (“true net metering”), the same rate that they charge customers for electricity. A recent Mason-Dixon poll of Floridians found 84% support the state’s current net metering policy.

Bradley’s bill would, in part, slowly scale the reimbursement rate down over the next few years — an approach she and House sponsor Rep. Lawrence McClure, R-Dover, are calling a “glide path” — to give the industry time to adapt to the changes. By 2028, at the end of that glide path, the rooftop solar reimbursement rate would be based on utilities’ “full avoided costs,” essentially the wholesale energy cost. The bill also gives utilities the ability to charge every customer more to recover any “lost revenues” associated with the addition of new rooftop solar systems installed between July 1, 2022, and Dec. 31, 2023. Customers who already have rooftop solar systems would be allowed to keep their current net metering rate for 20 years.

Florida Rep. Lawrence McClure on the House floor on March 4, 2021 | Florida House of Representatives

The ‘cost shift’ argument

Bradley, McClure, Florida utilities and other supporters of the bill say the change is needed because, they claim, under the current reimbursement rate, utility customers without rooftop solar are being forced to subsidize customers who have it.

“When (utilities) overpay for the excess energy produced by rooftop solar customers, you force the remaining ratepayers to pick up the rooftop solar customers’ share of grid infrastructure costs. This cost shift to non solar customers is substantial, and will shortly approach a billion dollars,” Bradley said during a committee stop. (She did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

FPL spokesman Christopher McGrath says solar customers are using the energy grid to sell power back to FPL, an energy grid that all customers pay for.

“Even if a rooftop system is capable of generating electricity equivalent to 100% of the customer’s consumption, FPL is required by law to incur costs to build and maintain infrastructure to provide full and instantaneous service to the customer when the sun is not shining or when the customer’s system is offline or otherwise unavailable,” he emailed ADAPT.

The goal of the bill, Bradley and McClure argue, is to prevent larger subsidies as Florida’s rooftop solar industry grows (Currently less than 1% of homeowners have panels installed).

Opponents of the bill argue the subsidy logic could be applied to utility customers who improve the energy efficiency of their home with new appliances or insulation.

“The other example you could look to is multi-unit dwellings, like an apartment building,” says Natalia Brown, Climate Justice Program manager with the Catalyst Miami advocacy group. “The multi-unit dwelling in that case is ‘subsidizing,’ if you will, the single-family home because it doesn’t take as much transmission infrastructure to reach what could be hundreds of units in that one building.”

Heaven Campbell, Florida program director for the Solar United Neighbors advocacy group, describes the “cost shift” argument as “unhinged.”

“They are basically saying any energy efficiency, any lack of consumption from us, is creating a cost shift,” she said. “It’s monopolies gone wild. Don’t even dare go on vacation.”

Solar panels on a Florida home | Glen Richard Photo via Shutterstock

‘Solar rooftop producers are subsidizing their neighbors‘

“The annual subsidy paid for by all FPL customers to support rooftop solar is approximately $30 million today. By 2025, that subsidy is expected to nearly triple to more than $80 million,” FPL’s McGrath told ADAPT.

When presented with those numbers, Western University Professor Joshua Pearce says, “I can say, with some gravitas, that I’m very certain that’s wrong.”

Pearce, the Thompson Chair in Information Technology and Innovation at Western University, is on a recently formed National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine committee that’s studying how net metering is evolving with the electric system. Much of his research focuses on the economics of solar panels.

“When you actually do all the math, there’s no question at all that when a customer puts in their own capital they protect the utility from having to put in their capital to produce the same amount of electricity,” he says. “The reason that many utilities are balking against net metering is because they’re a regulated industry — they’re usually guaranteed a 10% rate of return — and the only way they get that return is by investing capital.”

Pearce agrees that utilities’ infrastructure costs are a factor when calculating the costs and benefits of net metering — but they’re just one factor. One of his studies identified nine values of distributed-energy-generation systems like rooftop solar. Seven of those were seen as non-controversial, like high transmission capacity and low fuel cost. The two that are harder to quantify are environmental and health benefits.

Joshua Pearce, the John M. Thompson chair in information technology and innovation at Western University | Credit: Western University

“Solar rooftop producers are subsidizing their neighbors by just getting a net metering rate. They should actually be paid more,” he said. “When you start to add up the environmental and health costs, then the value of solar goes through the roof.”

Pearce and other opponents of the bill are urging the Legislature to commission an independent study to look at the pros and cons of the current net metering policy before enacting any changes, rather than depending on numbers provided by the utilities who would profit from a lower rooftop solar reimbursement rate. Several lawmakers proposed amendments to that effect, though they were rejected in the Republican-dominated House.

“We haven’t even researched if a subsidy exists,” said Rep. Anna Eskamani, D-Orlando, introducing an amendment on the House floor Tuesday. “We’re kind of operating on a he said-she said mentality. I really would prefer that we slow down, do the research and then decide on who actually loses. Based on the evidence in front of me today, I am concerned that those who lose are Florida’s people.”

Raina Greenfest (in yellow) in front of the Florida capitol. | Courtesy BayWa r.e.

What’s at stake for solar panel users

If Bradley’s bill becomes law, FPL expects its current reimbursement rate of about 12 cents per kilowatt hour to drop to somewhere between 3.6 and 4.8 cents. As ADAPT has reported, Jacksonville’s city-owned utility JEA enacted a similar net metering policy change in 2018, with existing rooftop solar owners being grandfathered in.

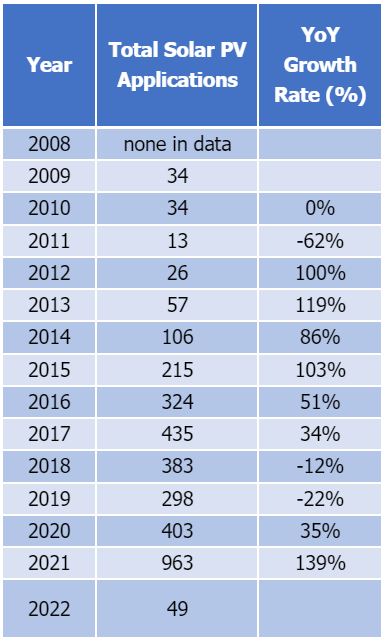

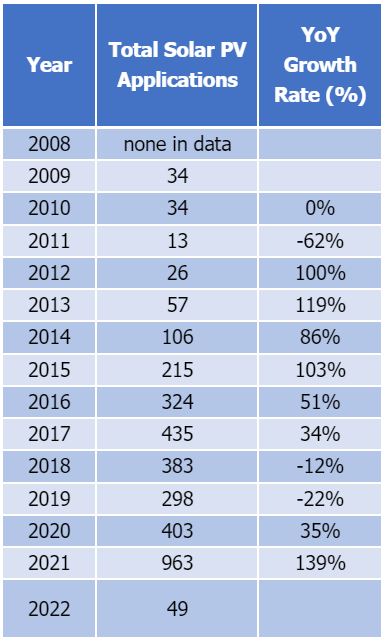

So, did JEA’s change kill rooftop solar, as advocates feared? In fact, it appears more Jacksonville residents want rooftop solar than ever before, according to installation data that JEA submits to state regulators.

In 2018 and 2019, the first years after the change, applications for solar panel work in Jacksonville took an immediate hit, but they recovered by 2020 to above the pre-2018 level and grew by 139% in 2021 alone — though JEA says the numbers include customers who add onto or replace old solar systems, not just new panel installations. JEA also reported to regulators it had 1,194 rooftop solar customers at the end of 2017 (the year before it dropped its reimbursement rate) and 2,172 as of Dec. 31, 2020.

JEA rooftop solar application growth. | Credit: JEA

Still, the economic benefit of owning solar panels is significantly less in Jacksonville today because of the change. Pete Wilking, founder of A1A Solar in Jacksonville, says it used to take seven to nine years for customers to recoup their investment on a rooftop solar system with a 35-year life. Now it takes about 20 years to recoup the cost. Wilking says after JEA’s net metering change, his business went off a cliff and he had to lay off half his staff.

Overall in Florida, the current net metering rate has helped rooftop solar grow by about 10,000% since the policy was enacted in 2008, according to Solar United Neighbors, though market penetration remains very low at less than 1%. Despite the fact that just 90,000 or so of the state’s 10.5 million electric utility customers have rooftop solar systems, the Florida Solar Energy Industries Association estimates that the state’s rooftop solar industry supports more than 40,000 jobs, including Greenfest’s.

“At the end of the day, I’m not just providing for my children but I’m also providing for their future by eliminating fossil fuels and pollutants and moving us towards a clean environment,” says Greenfest, who works for BayWa r.e., an international renewable energy company.

Similar changes to net metering have happened or are being considered across the country. In 2016 Nevada’s public utility commission allowed power company NV Energy to increase the monthly fee it charges rooftop solar customers and reduce its reimbursement rate. The rooftop solar industry crashed there virtually overnight, according to The Guardian.

After two years or so of public complaints, Nevada eventually reversed its decision and the industry has since bounced back to a certain extent. Rep. McClure, the House sponsor of the Florida net metering bill, says the Nevada policy failed because it was too sudden — it didn’t include the slow transition, or glide path, that the Florida proposal spells out.

California’s Public Utilities Commission is considering a similar, though more drastic change to net metering rules as well.

Editor’s note: Sen. Jennifer Bradley’s husband, former state Sen. Rob Bradley, is an opinion contributor to Jacksonville Today.

By Brendan Rivers

This article originally appeared on Jacksonville Today.

On Feb. 8, Raina Greenfest jumped on a bus from Palm Beach to Tallahassee to try to convince lawmakers to vote no. She wasn’t heading to Florida’s Capitol to rally against one of the controversial bills dominating national headlines this legislative session, like restrictions on abortion or race-based education. Rather, she was joining others from across the state who were organizing against a bill by Fleming Island Republican Sen. Jennifer Bradley — a bill drafted by utility giant FPL — that would significantly reduce the economic benefit of installing solar panels on our roofs.

For Greenfest, dubbed “Solar Mom” by her peers, opposition is personal. Her livelihood depends on solar installation. “I’ve been in the industry for 12 years. I can just say, from my bird’s-eye view, that we made history,” said Greenfest after the day in Tallahassee. “I’m pretty confident it was the largest gathering of solar workers in one place in Florida.”

Their voices weren’t persuasive in the Legislature. The measure passed the full House on Wednesday and is headed toward a vote in the full Senate.

Sen. Bradley — whose political action committee Women Building the Future received tens of thousands of dollars from Florida utilities this election cycle, including $22,500 from FPL’s parent company NextEra Energy — and others who support her bill say it would save all power customers money. Opponents say the hit to Florida’s fledgling rooftop solar industry further hinders the Sunshine State’s already slow transition to clean, renewable energy — what climate scientists say is urgently necessary if humans are to avoid the worst impacts of a warming world.

Florida Sen. Jennifer Bradley in legislative session on Jan. 12, 2022, in Tallahassee | Phelan M. Ebenhack, AP Photo

Net metering

Bradley’s bill would change the policy called “net metering,” which the Florida Legislature unanimously enacted in 2008. Net metering requires utility companies to reimburse rooftop solar customers for the extra energy they generate for the utility in the form of a credit on their power bill. Under current rules, the state’s investor-owned utilities are required to offer a one-for-one reimbursement rate (“true net metering”), the same rate that they charge customers for electricity. A recent Mason-Dixon poll of Floridians found 84% support the state’s current net metering policy.

Bradley’s bill would, in part, slowly scale the reimbursement rate down over the next few years — an approach she and House sponsor Rep. Lawrence McClure, R-Dover, are calling a “glide path” — to give the industry time to adapt to the changes. By 2028, at the end of that glide path, the rooftop solar reimbursement rate would be based on utilities’ “full avoided costs,” essentially the wholesale energy cost. The bill also gives utilities the ability to charge every customer more to recover any “lost revenues” associated with the addition of new rooftop solar systems installed between July 1, 2022, and Dec. 31, 2023. Customers who already have rooftop solar systems would be allowed to keep their current net metering rate for 20 years.

Florida Rep. Lawrence McClure on the House floor on March 4, 2021 | Florida House of Representatives

The ‘cost shift’ argument

Bradley, McClure, Florida utilities and other supporters of the bill say the change is needed because, they claim, under the current reimbursement rate, utility customers without rooftop solar are being forced to subsidize customers who have it.

“When (utilities) overpay for the excess energy produced by rooftop solar customers, you force the remaining ratepayers to pick up the rooftop solar customers’ share of grid infrastructure costs. This cost shift to non solar customers is substantial, and will shortly approach a billion dollars,” Bradley said during a committee stop. (She did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

FPL spokesman Christopher McGrath says solar customers are using the energy grid to sell power back to FPL, an energy grid that all customers pay for.

“Even if a rooftop system is capable of generating electricity equivalent to 100% of the customer’s consumption, FPL is required by law to incur costs to build and maintain infrastructure to provide full and instantaneous service to the customer when the sun is not shining or when the customer’s system is offline or otherwise unavailable,” he emailed ADAPT.

The goal of the bill, Bradley and McClure argue, is to prevent larger subsidies as Florida’s rooftop solar industry grows (Currently less than 1% of homeowners have panels installed).

Opponents of the bill argue the subsidy logic could be applied to utility customers who improve the energy efficiency of their home with new appliances or insulation.

“The other example you could look to is multi-unit dwellings, like an apartment building,” says Natalia Brown, Climate Justice Program manager with the Catalyst Miami advocacy group. “The multi-unit dwelling in that case is ‘subsidizing,’ if you will, the single-family home because it doesn’t take as much transmission infrastructure to reach what could be hundreds of units in that one building.”

Heaven Campbell, Florida program director for the Solar United Neighbors advocacy group, describes the “cost shift” argument as “unhinged.”

“They are basically saying any energy efficiency, any lack of consumption from us, is creating a cost shift,” she said. “It’s monopolies gone wild. Don’t even dare go on vacation.”

Solar panels on a Florida home | Glen Richard Photo via Shutterstock

‘Solar rooftop producers are subsidizing their neighbors‘

“The annual subsidy paid for by all FPL customers to support rooftop solar is approximately $30 million today. By 2025, that subsidy is expected to nearly triple to more than $80 million,” FPL’s McGrath told ADAPT.

When presented with those numbers, Western University Professor Joshua Pearce says, “I can say, with some gravitas, that I’m very certain that’s wrong.”

Pearce, the Thompson Chair in Information Technology and Innovation at Western University, is on a recently formed National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine committee that’s studying how net metering is evolving with the electric system. Much of his research focuses on the economics of solar panels.

“When you actually do all the math, there’s no question at all that when a customer puts in their own capital they protect the utility from having to put in their capital to produce the same amount of electricity,” he says. “The reason that many utilities are balking against net metering is because they’re a regulated industry — they’re usually guaranteed a 10% rate of return — and the only way they get that return is by investing capital.”

Pearce agrees that utilities’ infrastructure costs are a factor when calculating the costs and benefits of net metering — but they’re just one factor. One of his studies identified nine values of distributed-energy-generation systems like rooftop solar. Seven of those were seen as non-controversial, like high transmission capacity and low fuel cost. The two that are harder to quantify are environmental and health benefits.

Joshua Pearce, the John M. Thompson chair in information technology and innovation at Western University | Credit: Western University

“Solar rooftop producers are subsidizing their neighbors by just getting a net metering rate. They should actually be paid more,” he said. “When you start to add up the environmental and health costs, then the value of solar goes through the roof.”

Pearce and other opponents of the bill are urging the Legislature to commission an independent study to look at the pros and cons of the current net metering policy before enacting any changes, rather than depending on numbers provided by the utilities who would profit from a lower rooftop solar reimbursement rate. Several lawmakers proposed amendments to that effect, though they were rejected in the Republican-dominated House.

“We haven’t even researched if a subsidy exists,” said Rep. Anna Eskamani, D-Orlando, introducing an amendment on the House floor Tuesday. “We’re kind of operating on a he said-she said mentality. I really would prefer that we slow down, do the research and then decide on who actually loses. Based on the evidence in front of me today, I am concerned that those who lose are Florida’s people.”

Raina Greenfest (in yellow) in front of the Florida capitol. | Courtesy BayWa r.e.

What’s at stake for solar panel users

If Bradley’s bill becomes law, FPL expects its current reimbursement rate of about 12 cents per kilowatt hour to drop to somewhere between 3.6 and 4.8 cents. As ADAPT has reported, Jacksonville’s city-owned utility JEA enacted a similar net metering policy change in 2018, with existing rooftop solar owners being grandfathered in.

So, did JEA’s change kill rooftop solar, as advocates feared? In fact, it appears more Jacksonville residents want rooftop solar than ever before, according to installation data that JEA submits to state regulators.

In 2018 and 2019, the first years after the change, applications for solar panel work in Jacksonville took an immediate hit, but they recovered by 2020 to above the pre-2018 level and grew by 139% in 2021 alone — though JEA says the numbers include customers who add onto or replace old solar systems, not just new panel installations. JEA also reported to regulators it had 1,194 rooftop solar customers at the end of 2017 (the year before it dropped its reimbursement rate) and 2,172 as of Dec. 31, 2020.

JEA rooftop solar application growth. | Credit: JEA

Still, the economic benefit of owning solar panels is significantly less in Jacksonville today because of the change. Pete Wilking, founder of A1A Solar in Jacksonville, says it used to take seven to nine years for customers to recoup their investment on a rooftop solar system with a 35-year life. Now it takes about 20 years to recoup the cost. Wilking says after JEA’s net metering change, his business went off a cliff and he had to lay off half his staff.

Overall in Florida, the current net metering rate has helped rooftop solar grow by about 10,000% since the policy was enacted in 2008, according to Solar United Neighbors, though market penetration remains very low at less than 1%. Despite the fact that just 90,000 or so of the state’s 10.5 million electric utility customers have rooftop solar systems, the Florida Solar Energy Industries Association estimates that the state’s rooftop solar industry supports more than 40,000 jobs, including Greenfest’s.

“At the end of the day, I’m not just providing for my children but I’m also providing for their future by eliminating fossil fuels and pollutants and moving us towards a clean environment,” says Greenfest, who works for BayWa r.e., an international renewable energy company.

Similar changes to net metering have happened or are being considered across the country. In 2016 Nevada’s public utility commission allowed power company NV Energy to increase the monthly fee it charges rooftop solar customers and reduce its reimbursement rate. The rooftop solar industry crashed there virtually overnight, according to The Guardian.

After two years or so of public complaints, Nevada eventually reversed its decision and the industry has since bounced back to a certain extent. Rep. McClure, the House sponsor of the Florida net metering bill, says the Nevada policy failed because it was too sudden — it didn’t include the slow transition, or glide path, that the Florida proposal spells out.

California’s Public Utilities Commission is considering a similar, though more drastic change to net metering rules as well.

Editor’s note: Sen. Jennifer Bradley’s husband, former state Sen. Rob Bradley, is an opinion contributor to Jacksonville Today.